JavaScript Subroutines

Functions are Objects

One of the most important things to understand about JavaScript (and functional languages in general) is that all functions (a) exist as objects and (b) are dynamic. By comparison, there are compiled languages (e.g. Java) that have functions acting as class or instance methods, and are referenced with static locations. There are also languages (e.g. PHP) where functions are always present and you can call them even before the runtime parser has reached their definition (JavaScript actually has this ability too if you give a name to the function). So unlike other languages that use a compiler to turn functions and classes into a set of static routines, function objects don’t exist until the JavaScript parser has reached that line in the file.

First-Class Functions

Another aspect of JavaScript is that it has ‘first-class functions’ meaning that it supports:

- Passing functions as arguments to other functions

- Returning functions as values from other functions

- Assigning functions to variables or storing them in data structures

It also means that the names of JavaScript functions don’t have any special status; they are treated like ordinary variables with a function type. And by functions becoming objects, they are no longer a functionality hidden behind the compiler and a variable name; they are a ‘first class citizen’ of the page.

Subroutines

When the browser encounters a function definition, it saves the code in memory somewhere to be accessible for when it is needed later. It is essentially taking the function out of the main routine and making it a subroutine, storing the function through an Object that holds the code.

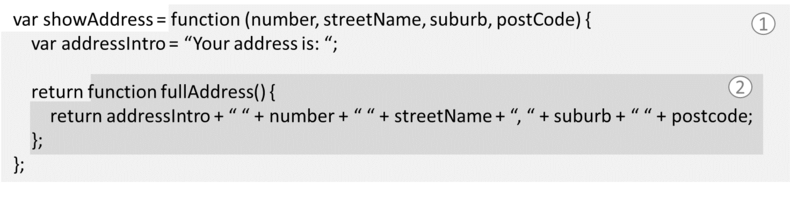

In the example below, the code from (1) is removed from the main routine and stored in a subroutine object that is assigned to the global showAddress variable. None of the code in (1) is altered in any way when this subroutine object is created. We can see the definition for (2) within this subroutine object. Until (1) is executed, (2) will remain a definition, and each time the (1) subroutine is called, it gets a new set of local variables or execution scope. This means that the values number, streetName, etc. that are passed to it are local to the code within the subroutine.

Now let’s execute the subroutine in (1):

var makeAddress = showAddress(42, “Wallaby Way”, “Sydney”, 2000);

showAddress();

It is now part of the main program, meaning that any function definition it encounters will be again removed from the routine and stored in subroutine objects. As the code in (1) executes, a new subroutine object is created for (2) with a new execution scope. Each time (1) is called, it removes the code in (2) and assigns it to a totally new subroutine object.

A Recursive Example

Another good use of subroutines is if you want to write a recursive function that starts with a variable declaration, like a data structure to store a cumulative result in. While you might not want to declare it in the global scope, you also can’t have it in the same scope as the inner code of the function because this would reset it each time. Let’s say we want to write a function that takes all of the keys of an input object and puts them into an array, and returns the resulting array. This object could have nested objects as its values:

var obj = {name: {firstName: ‘P’, lastName: ‘Sherman’}, age: 25, address: {number: 42, street: ‘Wallaby Way’, city: ‘Sydney;}};

var keysArray = function (obj) {

var results = [];

for (var key in obj) {

if (typeof obj[key] !== ‘object’) {

results.push(key);

}

else {

return keysArray(obj[key]));

}

}

return results;

};

The problem with this is that our results array is being reset each time we call keysArray. Using a subroutine we can avoid this issue:

var keysArray = function (obj) {

var results = [];

var subroutine = function (obj) {

for (var key in obj) {

results.push(key);

if (typeof obj[key] === 'object') {

return keysArray(obj[key]);

}

}

};

subroutine(obj);

return results;

};

Note: I have used concat rather than push in this second version, because concat joins the resulting subarrays together while push would nest them.